Regular readers of this blog and my #MuseumMonday feature will know that I love natural history. When visiting all the museums that I do, you tend to see the same information being presented in a very similar way. This can sometimes get a little boring and I sometimes wish that museums would spend the time and money required to review and update their signage/messaging. I recently visited a museum that bucks this trend, being quite vibrant and message focussed. This was the Crab Museum in Margate, Kent, which was founded in 2021 by brothers Bertie and Ned Suesat-Williams alongside sound artist Chase Coley. It is proudly billed as Europe’s first and only museum dedicated to crabs, which I think is extremely important. Situated in the upper floor of the Pie Factory building in Margate’s Old Town, the museum rejects traditional formats in favour of blending science, humour, philosophy, and activism. Having entered the museum, it was certainly a lot smaller than I expected it to be but they manage to pack a lot of content into a small space effectively.

Visitors are greeted by a timeline painted along the entrance corridor, which leads up to the main entrance of the museum. It is up here that the helpful and friendly staff welcome visitors before ushering them to encounter a series of displays ranging from fossils to fact-laden boards and whimsical models. The exhibits are quirky and playful: think oversized crab policemen in a 1950s horror film and amusing diagrams revealing unexpected biological facts, like how crabs urinate from glands on their heads. Alongside these comic touches, microscopes connected to screens allow visitors to observe parts of crabs they they wouldn’t normally get to see, such as their lifecycle or external anatomy. These opportunities create moments of real engagement for both children and adults, reinforcing positive associations with crabs rather than fearing them. I spent many a day as a child flipping rocks on the beach or out crabbing when the tide allowed, so it was great to get the inside scoop on crabs and consolidate some of the facts that were already floating around in the back of my head somewhere.

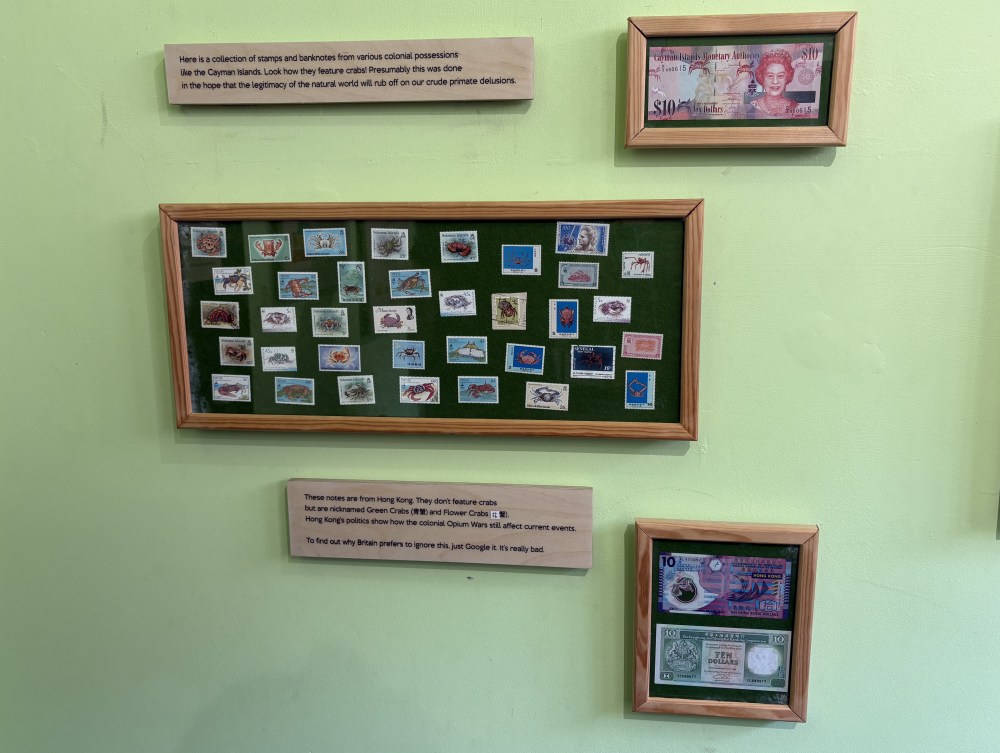

Humour is central to the museum’s appeal, with tongue-in-cheek signage, deliberate absurdities, and even a ‘World’s Funniest Crab Joke‘ competition judged by comedians such as Harry Hill and Rose Matafeo. Behind the silliness lies a deeper purpose: the museum addresses complex themes such as climate change, capitalism, colonialism, and even the philosophical role of museums themselves. The blending of comedy with serious ideas creates a distinctive atmosphere that manages to be entertaining while also thought-provoking. The Crab Museum also thrives online, where it has developed an unusual social media presence that won the Being Social category at the Digital Culture Awards in 2023. Its irreverent memes and surreal humour have been praised for sparking conversations about conservation and drawing in younger audiences. This community-minded, socially engaged approach sets it apart from larger, more traditional institutions and reinforces its grassroots identity. Feedback from visitors is overwhelmingly positive. Many describe the museum as hilarious, eccentric, and surprisingly informative, with staff often singled out for their passion and enthusiasm. Families especially appreciate the interactive exhibits, while others note that the museum is small but packed with ideas and fun. The gift shop, stocked with unusual, meme-inspired merchandise, is itself a source of delight. Not all reviews, however, are uncritical. I found it very fun and spent a fair bit in the gift shop (as I always do), and left with a smile on my face.

For a moment, let’s think about the location of the museum. This is probably no coincidence. In an extraordinary tale that straddles the line between local legend and whimsical folklore, the Margate Crab of 1862 was allegedly discovered by one Thomas Gaskell (a fisherman or oceanographer depending on the telling) who hauled in a colossal crab measuring some 2.5 metres (about 8 feet) in breadth. Instead of turning it into a showpiece or profit, Gaskell reportedly brought the creature into his home at Palm Bay, feeding it chopped eels as the creature curiously grasped objects in a strikingly intelligent manner. The story takes a darker turn: the crab’s presence incited public alarm, leading to a bizarre sequence of events involving an angry mob, a traveling freak-show, and even the death of a cruel circus master, eventually reducing the once-grand creature to a gruesome footnote. While the historical accuracy of this saga remains dubious, the tale is embraced by Margate’s quirky cultural narrative, blurring the boundaries between truth and imaginative spectacle.

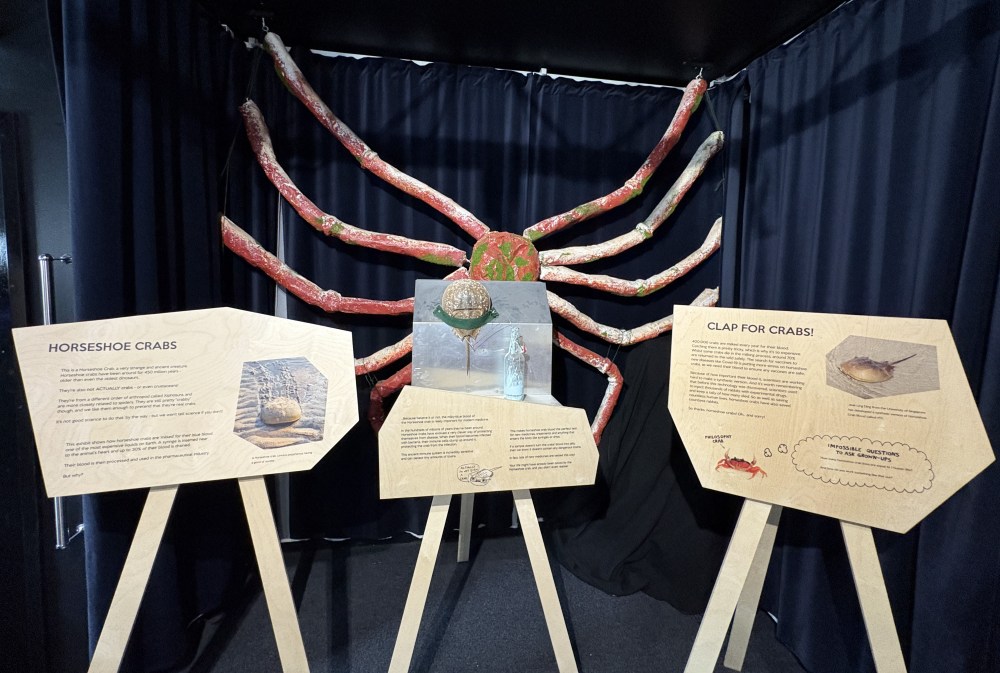

Something that was interesting to see on display was a horseshoe crab, which is only a crab in name. They are more closely related to arachnids like spiders and scorpions! The museum does a great job of highlighting the vital role in modern medical research and safety testing because their blue blood contains a unique substance called Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL). This compound is extremely sensitive to bacterial endotoxins, which are toxic substances that can cause dangerous reactions if present in vaccines, injectable drugs, or surgical implants. Since the 1970s, LAL testing has been the global standard for ensuring that medical products are free from harmful contamination, making horseshoe crabs indispensable to human health. Although synthetic alternatives are now being developed and approved in some regions, the reliance on horseshoe crabs remains significant, raising ecological and ethical concerns due to their declining populations and the crucial role they play in coastal ecosystems. Rightfully so, these unusual crustacean wannabes are getting some limelight and the recognition that they deserve.

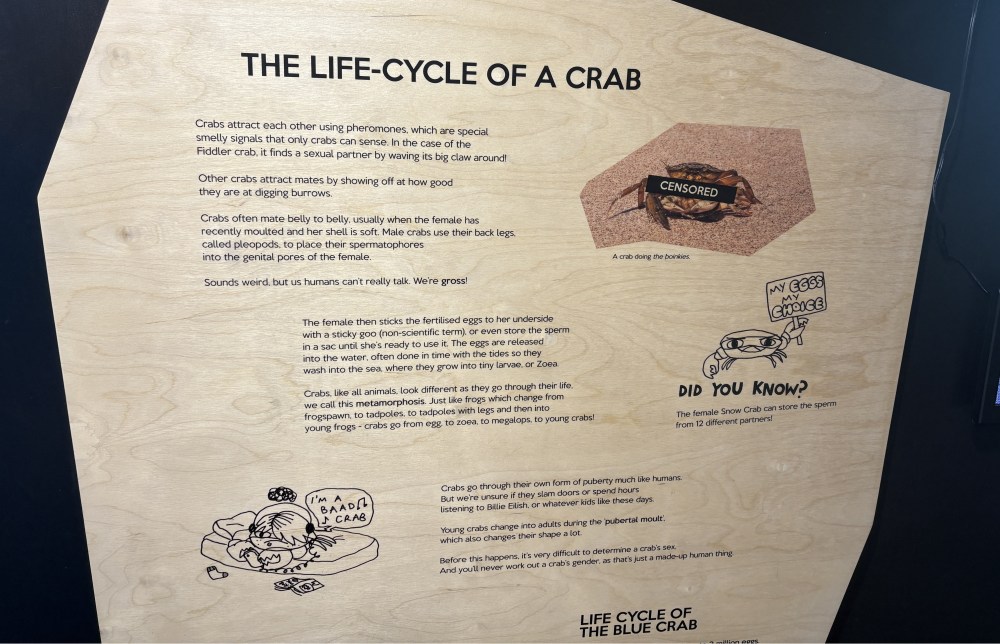

What is the lifecycle of a crab? Most people know as adults they live on beaches but what about the larvae? The museum has you covered! Crabs have a fascinating life cycle that includes several distinct stages of development, most of which occur in the ocean before they become recognisable as the crabs we see on beaches or in rockpools. It begins when females release eggs, which hatch into tiny larvae called zoea. Zoea are planktonic, meaning they drift in the water and feed on microscopic organisms. As they grow, they moult and pass through several zoea stages before transforming into the megalopa stage, which looks more like a small crab but still has a long tail-like structure. The megalopa eventually settles to the seafloor, where it undergoes another moult to become a juvenile crab, resembling a miniature version of the adult. Juvenile crabs continue to grow by moulting their hard exoskeleton several times until they reach adulthood. Adult crabs then reproduce, completing the cycle. The exact length and details of each stage can vary by species, but this general progression (egg, zoea, megalopa, juvenile, adult) is typical for most crabs. How amazing is that?

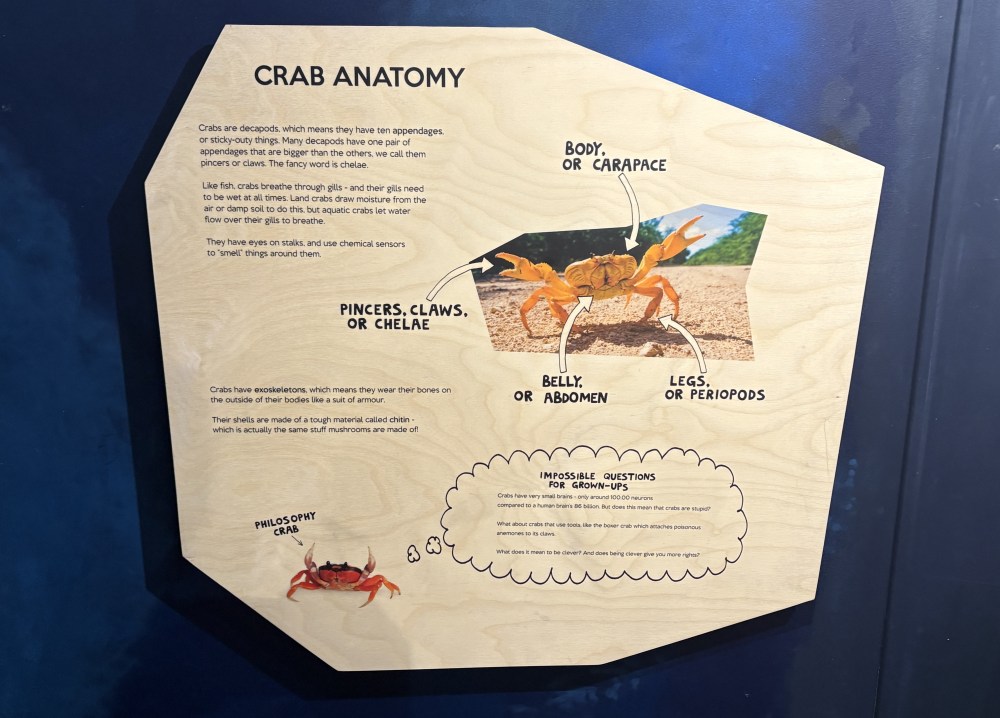

Chitin is a tough, flexible, and biodegradable biopolymer that forms the main structural component of a crab’s exoskeleton. This is something that some people may not know, and so the museum does a great job of explaining this to all ages, and they also have some chitin for people to feel. Tactile engagement is growing increasingly important in museums. Chitin provides strength and protection, allowing crabs to withstand predators and environmental pressures while still remaining lightweight enough for mobility. When crabs grow, they moult their chitinous shells and form new ones, a process that highlights chitin’s role in growth and survival. Beyond its importance to crabs, chitin has significant applications for humans: it can be processed into chitosan, a versatile material used in medicine, agriculture, water purification, and even biodegradable packaging. Thus, crabs and other crustaceans not only rely on chitin for survival but also contribute indirectly to advances in sustainable technology and healthcare.

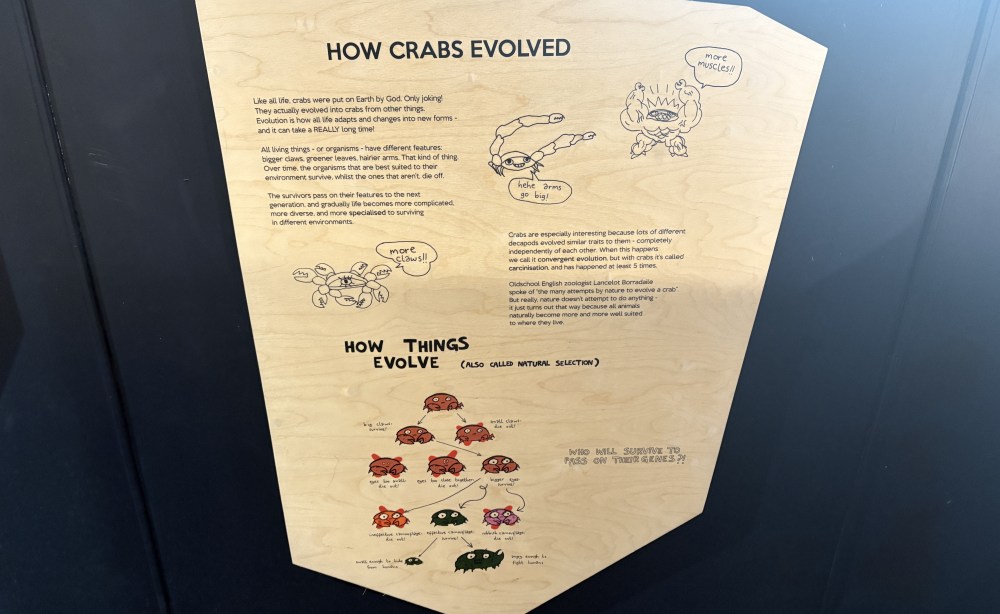

Crab evolution is a striking example of how similar body shapes can arise independently through a process called carcinification, in which crustaceans evolve a crab-like form multiple times. True crabs belong to the infraorder Brachyura, but several other groups, such as king crabs and porcelain crabs, have separately evolved flattened, rounded bodies with reduced abdomens tucked under the thorax, features that give crabs their distinctive shape. Scientists believe carcinification provides evolutionary advantages, including greater protection from predators, more efficient movement in tight spaces, and improved ability to burrow or cling to surfaces. This repeated emergence of the crab-like body plan makes carcinification one of the clearest cases of convergent evolution in the animal kingdom, demonstrating how natural selection can favour similar adaptations across unrelated lineages.

Crabton-on-Tyne is a playful, fictional seaside village created as part of a diorama. Set in the year 1926, the display imagines a world where crabs live like humans, complete with quaint hats, cucumber sandwiches, and all the trappings of English village life. Beneath its humour, Crabton-on-Tyne also nods to real social and political issues of the era, referencing movements like Bolshevism and women’s suffrage. By blending natural history with satire, the diorama encourages visitors to think critically about both human society and the cultural significance we project onto the natural world, all while enjoying the absurdity of crabs leading very human lives. Signage helps to describe each species of crab, their natural habitat but more importantly for diorama, their job and the activity they’re engaged with.

Some visitors have been surprised by the presence of pride flags and political messaging, which a minority feel jar with the scientific subject matter. The museum itself has responded by stating that museums are inherently political, a stance that may divide opinion. Given that the museum has collaborated with other modern museums such as the Vagina Museum, this shouldn’t be too surprising. Others point out practical limitations, such as the lack of live crabs, the compact size of the venue, and the current lack of wheelchair access, though there are plans to expand. I suspect the lack of live crabs is linked to ethical and welfare concerns. They should be left in the wild where they belong – the beach is only a few minutes walk away. Why not go and look for them there? Taken as a whole, the Crab Museum is a curious and original gem. Its strength lies in making science memorable through humour and irreverence, while also smuggling in serious reflections on society and the environment. For those willing to embrace its eccentricity and occasional politics, it offers a fresh take on what a museum can be. It is not a large institution, nor does it aspire to be but for anyone visiting Margate with an open mind and a sense of humour, it is well worth the stop.

Funded through donations, merchandise, and crowdfunding rather than corporate sponsorship, it remains free to enter and embraces its identity as a proudly independent, slightly chaotic institution. We need more smaller museums like this that are dedicated to a single group of animals that are usually overlooked or villainised in the media. Walking around the seafront of Margate, perhaps a Gull Museum is needed as herring gulls are on the red list and nine other species, including the black-headed gull and common gull are on the amber list of Birds of Conservation Concern in the UK. If a Gull Museum was able to undertake the same level of engagement, education and advocacy as the Crab Museum does, perhaps they wouldn’t be as vilified.

If you liked this post and enjoy reading this blog, please consider supporting me on Patreon where you will also gain access to exclusive content. If you enjoy reading my blog, why not subscribe using the form below?