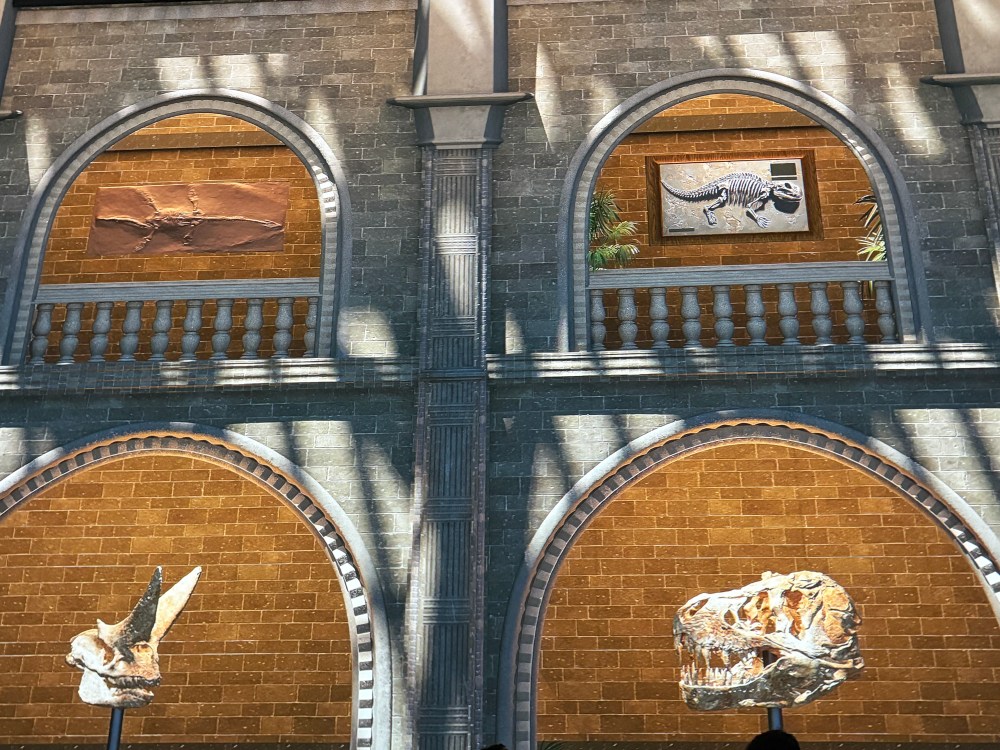

At heart, I am just a big kid (if that wasn’t already obvious). One of my passions outside of herpetology that helps to satisfy my inner childhood curiosity, is palaeontology. I am lucky enough to have published my first paper in the field earlier this year, with more planned thanks to an excellent network of collaborators. Therefore, given the opportunity to meet up with some of my friends and colleagues that share a similar passion to go and experience Discovering Dinosaurs at Lightroom, was a no brainer. I hadn’t heard of Lightroom prior to this showing but it was quite the experience. Stepping into the vast cuboid hall of Lightroom, which is nestled just behind King’s Cross Station, London, you are surrounded on all sides (walls, floor, and sometimes ceiling) by sweeping, high-resolution CGI of dinosaurs (and other prehistoric species) in motion. The show lasts approximately 50 minutes and is narrated by actor Damian Lewis, with an original score by Hans Zimmer. It felt criminal to not have Sir David Attenborough reprising his role from Prehistoric Planet (which Discovering Dinosaurs is a spin-off of), but rumour has it that he is in the process of retiring so that is completely understandable.

So, what is Discovering Dinosaurs all about and why should people visit? The experience is broken into six themed segments (or ‘mini-documentaries’), giving it structure and a beginning-to-end flow rather than just a single continuous stream (later I’ll summarise each segment). While clearly designed with families and children in mind, the show also provides enough spectacle and science for curious adults too. That said, as I’ll discuss, it sometimes trades depth for breadth in its aim to engage all ages. What sets it apart is the sheer immersive scale: dinosaurs are shown at life‐size, sometimes four stories tall, moving across deserts, with mosasaurs in the oceans and pterosaurs in the skies. From the moment you enter, the visual and sonic design hit hard. You feel dwarfed by the creatures around you, you are invited to stand next to a giant Tyrannosaurs rex, measure yourself against a sauropod, see the scale of prehistoric life in a visceral way. This helps to put the sheer scale of these animals into prospective, it isn’t often that I am made to feel small!

The CGI is excellent, it is pin-sharp photorealist which helps to increase the realism of the experience. The fact that this is not simply a standard flat film but an enveloping 360° environment means that even adults familiar with dinosaur documentaries may still feel a moment of wonder (myself included). On the other hand, there are compromises. You may feel your neck straining because you’re looking up or around constantly, or get pretty uncomfortably pretty quickly as there is a lack of seats, so you’ll have to cope with sitting on the floor for an hour. Furthermore, the science content is broad brush to ensure it is as accessible as possible, rather than deeply technical. The show assumes a general audience rather than specialist palaeontologists, which I complete understand, but there are a few elements that could have been improved. An example is that mosasaurs are referred to as marine lizards, without any further explanation.

As previously mentioned, there are six sections that make up Discovering Dinosaurs. Each section explores a different dimension of dinosaur life, evolution, their interplay with Earth’s changing environments and our developing understanding of them. I’ll take each in turn, discuss what the show offers, and reflect on how well it explores the evolution of dinosaurs and our understanding of them. I’m also going to provide as little visual examples as possible as to not spoil the overall experience, which I hope you’ll appreciate. Before that though, why might people visit? Discovering Dinosaurs offers a rare chance to experience the prehistoric world on an awe-inspiring, immersive scale. Instead of watching a flat documentary, visitors are surrounded on all sides by enormous, lifelike dinosaurs projected in ultra-high definition, moving, hunting, and interacting in their natural environments.

The opening chapter titled Age of Giants plunges the viewer into the Mesozoic world including vast deserts, deep seas, soaring skies, and introduces us to dinosaurs at their peak: the enormous sauropods, the apex predators, as well as the giant marine reptiles that also ruled the oceans at the same time. The visual impact emphasises size and spectacle: standing next to a four-storey tall beast conveys something of the scale of life on Earth before humans. Seeing the skeletons of these dinosaurs in a museum is one thing, but being able to see the animals as they would have been in life is a whole other experience. From an evolutionary perspective, this segment introduces the concept of dinosaur dominance: that during the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, dinosaurs proliferated into a wide range of ecological roles, growing large and diverse. While the script doesn’t give a detailed taxonomic rundown, it conveys the broad message: these were not uniform beasts. In terms of our understanding of them, the show uses modern CGI informed by the latest palaeontology, for instance feathered raptors, realistic locomotion, accurate environments (though drawn from the series). This helps the audience update older mental images of dinosaurs as only scaly monsters.

The second section titled The Tree of Life broadens the lens: dinosaurs are placed within the broader tree of life, their origins, links to modern birds, and the branching of evolutionary lines. Here the narrative begins to ask “where did they come from?” and “how are they related to us (and modern animals)?”. The show uses fossil evidence, animations of evolutionary transitions, and comparisons between extinct dinosaurs and living creatures (for example, birds and crocodiles). This connects dinosaur evolution to contemporary life and emphasises continuity rather than wholly alien creatures. The name The Tree of Life suggests a conceptual framing: evolution as branching, as change over time, not static. That message is important: dinosaurs did not simply appear fully formed and stay the same until extinction, they evolved and filled as many niches across the planet as possible.

The third chapter titled Raising the Young focuses on dinosaur reproduction, parenting, growth, and life-cycles. Viewers see egg-laying, hatchlings, juveniles, family behaviour and survival strategies. Visually and narratively, this is compelling: small dinosaurs move alongside or are cared for by adults; scenes of nesting, hunting for food, escaping predators. These narratives humanise the creatures somewhat and make them more relatable. Evolutionarily, this segment emphasises life‐history strategy: not just size and predation, but survival of the young, investment in offspring, changes in developmental timing (ontogeny) that palaeontologists recognise in dinosaur fossils (e.g. growth rings in bones, development of feathers, juveniles behaving differently). The show simplifies this but it does mention that our understanding of dinosaur life-cycles has changed (for example, that many dinosaurs had feathers or parental care). There are of course a number of sequences from Prehistoric Planet that play out during this section that highlight these relationships.

The fourth chapter is one of the more interesting and slightly meta chapters: it deals with how dinosaurs are perceived in human culture, the monsters of popular imagination, and how our understanding has shifted. Fittingly titled Monsters in the Mind, it touches on the idea that dinosaurs haunted our imaginations (as Lewis says: “close enough to haunt us, far enough not to hurt us”) before we had even discovered their bones. The show uses footage of dramatic hunts, predation scenes, but also signals that many popular images (e.g. scaly, slow, tail-dragging) are outdated. It invites viewers to reassess their mental image of dinosaurs and other extinct reptiles from the Mesozoic. From an evolutionary science perspective this chapter is less about the dinosaurs themselves and more about our science of them: how fossil discoveries, improved imaging, and behavioural inference have changed what we know about these animals. For example, that many dinosaurs were feathered; that birds are living dinosaurs; that some ‘monsters’ were more nuanced creatures of ecosystem. It’s a clever chapter because it appeals to adults and older children who have been raised on dinosaur media; it offers reflection.

The penultimate chapter Unearthing the Past, gets more directly into palaeontology: fossils, the processes of fossilisation, the detective work of scientists, how we reconstruct behaviour from bones, tracks, and other evidence. Visually you see animations of digging, bone reconstruction, sediment layers, comparisons between skeletons and living animals (homology). This helps ground the spectacular CGI in scientific reality. From the evolutionary viewpoint, this segment reinforces that our picture of dinosaurs is built by inference: phylogeny, cladistics, comparative anatomy, trace fossils, isotopic analysis. The show doesn’t dwell on the deep technicalities but does succeed in giving a sense of “we know this because…”.

All of this helps the audience appreciate the scientific method, uncertainty, and how knowledge evolves (pun intended) through time. That helps mitigate the view that dinosaurs are just facts to be memorised, instead emphasising they are the subject of ongoing research.

Patterns in Evolution, is the final chapter which draws conclusions from the previous five chapters, including patterns of rise and fall, adaptation, extinction, and legacy. It discusses how dinosaurs responded to environmental changes, competition, and how some lineages survived (birds) while others did not. It also touches on the mass extinction event ~66 million years ago and the aftermath. The title suggests a zoom-out: from individual species to big picture, including how we are in the process of fuelling the next mass extinction as a species. This is where the show emphasises macro-evolution: radiations, convergences, disappearance, and survivorship. For example, why did large dinosaurs thrive for tens of millions of years, and why did they suddenly vanish (for the non-avian ones)? What patterns in environment, physiology, ecology contributed to this? In terms of our understanding, this part prompts reflection: our planet has changed; life adapts; extinctions happen; humans are only a moment in geological time. It also subtly invites us to consider current biodiversity, our own role in shaping future evolution or extinctions. While the show is not an overt environmental treatise, the legacy of dinosaurs as part of Earth’s history is implicit. Thus, this final chapter brings together spectacle, science, and reflection.

Across its structure, the show does a commendable job of charting the evolutionary story of dinosaurs and other prehistoric reptiles. It opens with dinosaur dominance (Age of Giants) and then situates them within the broader evolutionary tree (The Tree of Life). It follows life-history and behaviour (Raising the Young), showing that evolution is about survival, not just size. It examines how our perceptions have evolved (Monsters in the Mind), signalling that our fossil-based picture has grown more refined. It gives insight into palaeontology and scientific inquiry (Unearthing the Past), emphasising how we know what we know. Finally, it closes with patterns of change, adaptation, extinction and legacy (Patterns in Evolution). In doing so, it weaves several evolutionary themes: diversification (radiation), adaptation (behaviour, habitat), extinction (demise of non-avian dinosaurs), survivorship (birds), convergence (similar ecological roles across eras) and our human place in the story.

Importantly, even though the show is simplified for accessibility, it introduces audiences to key palaeontological understandings: e.g. that many dinosaurs had feathers, that birds are their modern descendants, that dinosaur life-history was complex, that fossil evidence is partial and interpreted. In short: if you’re looking for an immersive blockbuster of dinosaurs, it delivers. If you’re after highly detailed new scientific research, you may find it doesn’t dig as deep as purely academic offerings. The immersive format reinforces the evolutionary message: you are not merely watching pictures; you are surrounded by the products of 200+ million years of evolution. That embodied experience adds a layer of impact. The venue and ticketing are premium, with adult tickets costing £25, which may not be worth it if you’re not happy to sit on the floor as seating may be limited during your showing.

Something that I wasn’t expecting to see during Discovering Dinosaurs because it isn’t related to them, is Joel Sartore’s Photo Ark. This is a remarkable global project that blends art, conservation, and storytelling to document the diversity of life on Earth before it disappears. Launched in 2006 in partnership with the National Geographic Society, the Photo Ark aims to photograph every species living in zoos, aquariums, and wildlife sanctuaries worldwide, an estimated 20,000 animals in total. Some of Sartore’s distinctive photos were shown while highlighting the current global extinction crisis. Sartore’s style places each creature against a simple black or white background, removing distractions and giving equal dignity to every subject, from tiny insects to endangered elephants. This approach humanises animals, allowing viewers to connect with individual faces and personalities while confronting the urgency of biodiversity loss.

So, what works and what could be improved? Seeing dinosaurs at life-size, in 360°, with surround sound, is a rare treat. High-end CGI, original scoring, and design tailored to the venue make the show feel premium. The six-chapter structure helps laypeople follow the story of dinosaurs, evolution and science. It also allows people to come and go at different times, which can also be a bit distracting. The show remains engaging for children but still offers educational substance for older visitors. Finally, Lightroom offers a modern space, good location (King’s Cross) and a novel way to experience dinosaur content. However, for visitors already well-versed in palaeontology, the show may feel surface-level. The 360° environment means you may strain your neck looking around; seating may be limited; the audio narration is sometimes noted as too quiet or difficult to follow (even with sub-titles). For the price, I was expecting something a little more scientific although I still enjoyed the experience. As it’s open age and many younger children attend, some may find the environment noisy or distracting (children running around floor projections). Finally, the show sometimes emphasises spectacular visuals over deep explanation; some may prefer a more measured documentary format.

If you are in London and have even a mild interest in dinosaurs, science or immersive experiences, this is well worth a visit. For families especially, the show offers a ‘wow’ factor and a memorable way to experience the prehistoric world. For adults, even if you’ve seen many dinosaur documentaries, the scale and surround nature give a fresh twist. If you are a serious dinosaur enthusiast or a palaeontology student, you may find the show entertaining but not ground-breaking in scientific terms. In that case, you might pair the visit with follow-up reading or a deeper documentary afterwards. I’d suggest choosing a time slot less likely to be crowded (perhaps weekday morning) so you can sit and absorb the visuals without distraction. Also, arrive early to get a good seat (perhaps near a corner where you can relax your neck). Consider snacks beforehand since comfort might matter when you’re looking upward and around for ~50 minutes.

In sum, Prehistoric Planet: Discovering Dinosaurs at Lightroom succeeds in bringing dinosaurs back to life not just as roaring monsters but as evolutionary marvels, as part of Earth’s story, as creatures whose legacy still resonates. Through its six-part structure it takes you from the giant beasts of the Mesozoic to the scientific methods that uncover their world, and finally to the patterns in evolution that connect them to our present. While it may not replace a dedicated palaeontology lecture or a specialist documentary in depth, it strikes a commendable balance of spectacle and science. The immersive environment adds a layer of engagement that conventional screenings don’t provide, and the six chapters give visitors a coherent narrative arc rather than a collection of random scenes. If you leave feeling a little more curious about dinosaurs, or a bit more humble about humanity’s short time on Earth, then the show has done its job.

If you liked this post and enjoy reading this blog, please consider supporting me on Patreon where you will also gain access to exclusive content. If you enjoy reading my blog, why not subscribe using the form below?