If you love museums that feel like friendly encyclopaedias of a place where local history, natural history, art and a surprisingly global collection rub shoulders in a handsome old building, then the Hastings Museum & Art Gallery is a quietly exceptional museum. Tucked behind Bohemia Road in Hastings (East Sussex), it wears its civic pride openly: free entry, strong school and community programmes, and a willingness to display unusual objects from across the world alongside very local treasures. The museum’s mix of ‘big idea’ galleries (such as dinosaurs or world cultures) and deeply local displays (the story of Hastings from prehistory to the present), makes for a visit that has many little epiphanies rather than one grand spectacle. It also allows visitors from outside of the local area to learn more about the history of Hastings and how it aligns to my own interests. If you’re planning a visit, I’ve written this as both a guided tour and a critical appreciation, doing my best to point out highlights, contextual significance, and a few ways the museum could push further.

The museum occupies a handsome 1920s municipal building with a high, wood-panelled central hall that still reads as an Edwardian civic interior. The architecture matters. The scale and oakwork lend gravitas to the collections, and the layout, a series of rooms that step down into subject-specific galleries that encourages exploratory wandering rather than a forced chronological march (I may have accidentally completed some of the galleries in reverse). The museum’s welcome is practical and warm: free entry, parking, and clear signage throughout which I am sure make it a favourite local destination. While the building gives the museum an institutional feel, the displays are refreshingly human. Cases contain letters, local posters, tools, and objects people recognise, and alongside them are fossils, Native American beadwork, and paintings that remind you Hastings has always been a place of trade and movement, not just an isolated seaside town.

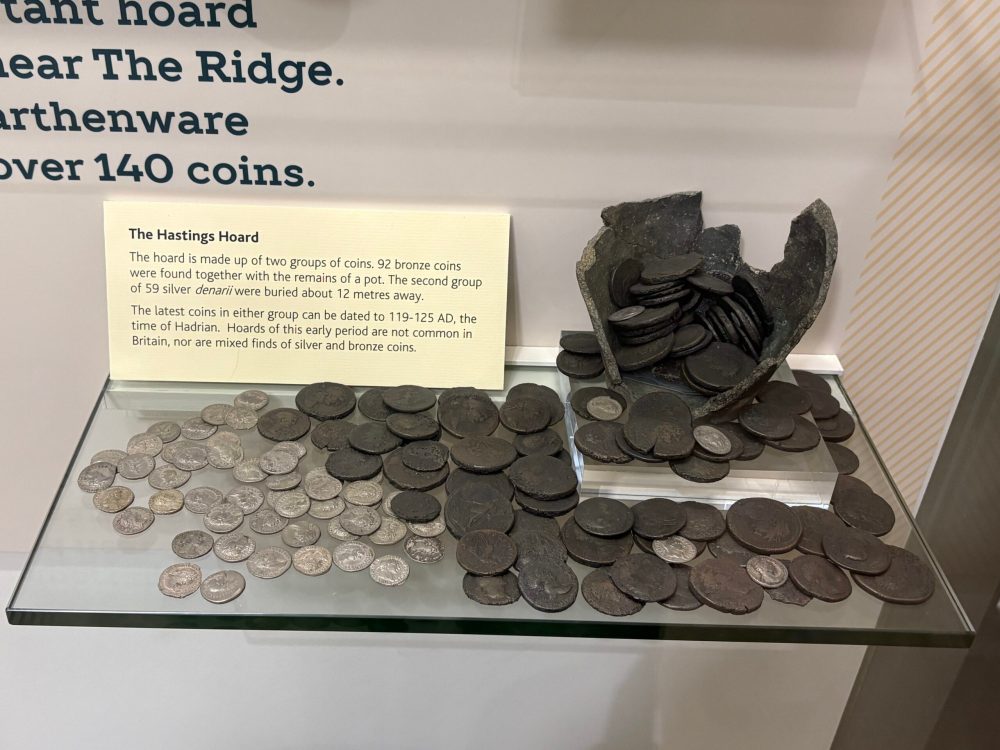

Before Hastings is one of the museum’s newer interpretive galleries. Rather than start with a generic ‘prehistoric objects’ case, the gallery frames prehistory as the deep backstory of the place: changing sea levels, early settlements, and the geology that would later preserve fossils. The gallery combines hands-on interactives and explanatory panels with key objects: local flints, pottery sherds, and small finds that anchor the narrative in the physical landscape around Hastings. Why does this matter? It roots local identity in deep time. For residents and visitors alike, seeing evidence of Mesolithic and Bronze Age activity in the same coastal strip that hosts the modern town collapses the sense of novelty and underlines continuity. The displays are curated so the ‘ancient’ becomes local and specific rather than abstract prehistory, a very effective interpretive choice.

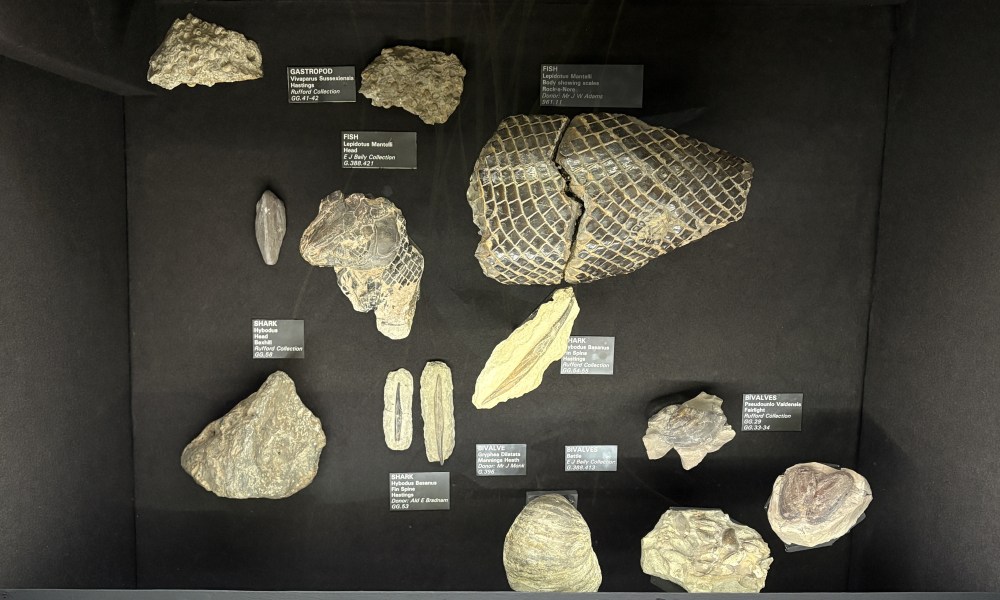

One of the most crowd-pleasing rooms is the dinosaur/fossil gallery. East Sussex sits on Cretaceous chalk and sandstone beds that have produced important fossils; the museum uses local geology as a hook to explain broader palaeoecological themes (climate, sea levels, and the kinds of creatures that once roamed the region). Expect fossil fish, marine reptiles, and interpretive panels that place Hastings within a 140-million-year-old landscape. There are also family-friendly interactives that make the science accessible to younger visitors. While the museum does not claim a national blockbuster dinosaur skeleton, its fossil collection’s strength is locality, specimens recovered from the cliffs and foreshore that tell a very local palaeontological story. For local residents, seeing material dug up on nearby beaches or preserved in local strata creates a personal connection to deep time, and for fossil-hobbyists, it’s a useful, well-documented regional resource. In my mind, the gallery is a good example of how a local museum can leverage regional geology to deliver both education and place-based pride.

Who collected these fossils? The museum tells the story of the men who contributed to our understanding of the fossils in this area. The first of these is Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955) who was a Jesuit priest, philosopher and geologist who, while studying theology at Ore Place near Hastings between 1908–1912, became fascinated by the local Wealden clay and coastal cliffs. He and a fellow student, Felix Pelletier, collected around 150 plant and animal fossils locally, many of which he donated to Hastings Museum. The second is Edward John Baily (1859–1939), a brewery owner, who amassed over 650 fossil specimens from sites including Hastings, Darvel Beach, Telham, Archer Wood and Higham, his collections also contributing significantly to the local museum. Finally is Philip James Rufford (1852–1902) was a civil engineer and keen geologist whose Wealden plant‐fossil collection, taken mostly along the coastline from Rock‐a‐Nore to Cliff End (Fairlight) which is considered one of the most important of its kind. Parts of it went to Hastings Museum and other parts to the Natural History Museum. Together, these three fossil hunters helped build the fossil collections of Hastings, contributing both specimens and local geological knowledge, helping to preserve material that continues to inform studies of the Wealden flora and fauna.

The Story of Hastings in 66 Objects is a gallery that This is the museum’s attempt to tell the town’s story through emblematic objects, a curatorial approach that’s both popular and effective because objects act as narrative anchors. The gallery’s ’66 objects’ format is intentionally bite-sized, each object tells a strand of social, cultural or economic history from medieval times through Victorian tourism to wartime and the post-war seaside economy. Highlights include: maritime artefacts (ropes, ship fittings), civic regalia, fishing implements (Hastings’ fishing industry, particularly the iconic tall, netted ‘net shops’ on the Stade is essential to local identity), and ephemera from the Victorian seaside era (postcards, posters, and souvenirs). The selection includes personal letters and photographs that give texture to the big themes. Why this is important? Narrative object-based displays are terrific at showing how national stories (industrialisation, empire, wartime mobilisation) play out locally. For Hastings, a town known in tourist brochures for 1066 narratives and its seaside, the gallery shows a more complex history, fishing, trade, and cultural exchange which is valuable for residents who want a fuller account of their town’s past.

The Hastings Museum and Art Gallery has a long tradition of natural history collecting and presents wildlife through a combination of specimens, dioramas and interpretive text. The dioramas are classic in style, with taxidermy posed in recreated habitats to show local species in context. These range from coastal birds to woodland mammals, and they’re useful both for budding naturalists and for older visitors who appreciate the craftsmanship. In a region where habitat change and conservation are pressing concerns, the gallery functions as both a historical record (species that were common or rare in the past) and as a prompt for conservation discussion. The museum’s approach puts species into place, not as isolated curiosities but as parts of the local ecosystem. There are also helpful books here to engage visitors of all ages with the specimens.

Possibly the museum’s most surprising asset is its substantial Native North American collection, displayed across three galleries. This collection includes Plains and Sub-Arctic material: beadwork, clothing, tools, and ritual items. The galleries also foreground the local connection to Grey Owl (Archibald Belaney), the early 20th-century conservationist and writer who was born in Hastings before moving to Canada and becoming famous (and later controversial) as a voice for conservation and Indigenous rights. The museum uses the Grey Owl connection as a bridge between global stories and local biography. It is rare for a provincial English museum to hold and interpret such a fine group of Native North American objects. The displays are handled sensitively, with ethnographic labels that explain materials, use, and provenance. They raise important interpretive questions about collecting histories and colonial connections, a subject the museum appears to address by contextualising the objects and their acquisition histories rather than simply aestheticising them. These galleries are a reminder that ‘local museum’ does not always mean parochial. Hastings’ maritime history and 19th/20th-century travel networks contributed to collecting networks that brought global artefacts to the town. The museum’s job (and it largely does it well here_ is to interpret those items responsibly and in dialogue with contemporary debates about display, repatriation and interpretation.

The Sub-Arctic Gallery at is part of the Native North American collection, focussing on the peoples and cultures of the sub-Arctic regions. It features objects collected from sub-Arctic Inuit and related groups, alongside displays that explore the natural environment, artistic practices, tools and daily life in these very cold climates. The gallery is carpeted and has low lighting to help preserve the artefacts, and some items are displayed at lower heights to make them more accessible. Visitors moving through it transition to the Natural History gallery or the Plains Gallery. It is a shame there isn’t more signage in this gallery to help visitors to interpret the various different items on display.

Beyond the Native North American suite, the museum’s world cultures holdings are broad: African, Asian, Oceanic and other objects collected through Hastings’ maritime connections and through donations. The displays are neither exhaustive nor purely encyclopaedic, instead, they tend to present key objects alongside contextual material that explains trade routes, collecting histories, and colonial-era networks. The world cultures rooms offer fascinating material culture (masks, textiles, and ritual objects) but they also force curators to tackle difficult provenance questions. The museums generally presents these objects with interpretive notes about how they came to Hastings and with sensitivity to the ethical questions museums face today. This is an area where continued community and scholarly engagement will be important. These are housed upstairs in the Durbar Hall, which we’ll visit again shortly.

The Durbar Hall is a striking feature of Hastings Museum & Art Gallery, evoking the grandeur of 19th-century colonial display. Originally constructed in 1886 for the Indian & Colonial Exhibition in London, the hall formed the centrepiece of a replica Indian palace designed by Caspar Purdon Clarke and hand-carved in teak and deodar cedar by skilled artisans Mohammed Baksh and Mohammed Juma from the Punjab. After the exhibition the hall was acquired by the Brassey family, and in 1919 was donated to Hastings, where it was reconstructed as part of the museum in the early 1930s, restoring much of its former elegance. Today the hall spans two floors under a lantern roof; its ground floor is used for civil ceremonies, performances, talks and small gatherings (seating up to about 70–80 people), while the upper floor houses displays from world cultures, forming part of the museum’s galleries. The hall’s ornate woodwork and stained-glass windows, its arches and balcony staircases, make it one of Hastings’ most beautiful and historically resonant interiors.

The art collection at Hastings is broad: Victorian portraits and landscapes, local topographical painting, and works by artists with regional connections. The museum’s art gallery balances the expected seaside landscapes with more unexpected pieces, Victorian genre painting, modern works, and decorative arts such as ceramics and metalwork. Artists who painted the Sussex coast and countryside are well represented, which helps visitors see the region through historical eyes, how artists perceived light, industry, and leisure. The decorative arts displays (ceramics, glass) reflect the town’s social history: domestic objects, commemorative ceramics, and material culture that reveal taste, trade connections, and local manufacture.

The Ceramics Gallery is devoted to both historical and artistic ceramic works, giving visitors insight into pottery, earthenware, porcelain and other clay-based objects spanning various periods. It sits on the first floor, accessible by stairs (or lift), with carpeted flooring and display cases and information panels arranged to allow different display heights, alongside seating to encourage lingering. The gallery bridges the past and present, not merely showing heritage pottery and decorative ceramics but also celebrating local craftsmanship and artistic expression. The mood is bright and welcoming compared to some of the darker, low-lit galleries within the museum (mainly to ensure the longevity of specimens/artefacts), allowing colours and glazes to be appreciated in detail.

The Brassey Gallery showcases the legacy of Thomas Brassey and Lady Annie Brassey, especially their world-travelling, collecting, and patronage. The gallery holds many of the ethnographic, artistic and natural history objects Lady Brassey gathered during voyages aboard their steam yacht Sunbeam, from places such as Japan, India, Oceania and beyond. The Sunbeam itself was a luxurious and well equipped steam-assisted three-masted yacht launched in 1874, built for long voyages, with both sailing rig and an auxiliary steam engine. Lady Annie Brassey chronicled life aboard Sunbeam in writings and photographs, including a best-seller A Voyage in the Sunbeam: Our Home on the Ocean for Eleven Months. Hastings The objects she collected, and the story of Sunbeam’s voyages, form a major part of the cultural heritage displayed in the Brassey Gallery, helping visitors see how global exploration, Victorian travel writing, and collecting practices shaped museums like Hastings.

Seaside: Wish You Were Here is a gallery that traces the evolution of Hastings as a seaside resort, showing how tourism, fashion, leisure and youth culture shaped the town’s identity over time. One of its highlights is a display on the 1960s youth subcultures Mods vs Rockers, exploring how Hastings featured in what has become known locally (and in media) as the ‘Second Battle of Hastings’, when clashes between Mods on scooters and Rockers on motorbikes over Bank Holidays created moral panic and dramatic headlines. The exhibition uses objects, photographs, ephemera and local testimony to capture both the glamour and tension of seaside culture: the deck chairs, the promenade, the cafes, the music, and how people came to the coast for escape and identity. Through Seaside: Wish You Were Here, visitors see not only the big events but everyday holiday-life: bathing machines, ice creams, bandstands, beachwear, postcards and amusements, all showing how the seaside shaped social life, fashion and community in Hastings.

The museum does social history well, domestic interiors, oral histories, work tools, and wartime material. Special attention is paid to Hastings’ wartime experience (evacuations, local defence, and the role of the port) and to the seaside’s 20th-century identity, the highs of Victorian and Edwardian holidaymaking, the mid-century challenges, and contemporary regeneration. Notable small items include personal diaries, school photographs, and household items are displayed with clear labels and, often, first-person voices taken from oral-history archives. This approach helps the museum be less of a cabinet of curiosities and more of a community memory bank.

The museum also functions as a research resource: its archives, photographic collections, and object databases are used by local historians, genealogists, and researchers interested in natural history and world cultures. The museum runs school workshops, family art sessions, and community outreach that use the collections as teaching resources. Their education suite and loan-box programmes extend the museum into classrooms. In an era when local museums face budget pressures, Hastings has made education and accessibility central to its mission. The museum balances permanent displays with rotating exhibitions that broaden the museum’s scope. This programming keeps the museum dynamic, a place where regular visitors can discover something new. The contemporary art shows, in particular, create a productive tension between heritage displays and living cultural practice.

There are many strengths of the museum. The first of these is a local specificity married to global reach. The museum is rooted in place (prehistory, seaside, civic life) while also hosting a surprising global collection (notably the Native North American material). That combination makes it layered and interesting. It is also an important and accessible educational facility with free admission and active school programming which help it to be public-facing and engaging at the same time. Most importantly for me and this blog, there is a strong natural history strand. Local fossils and wildlife displays give the museum an identity that reaches beyond human history into geology and ecology. It is a shame this couldn’t occupy the entirety of this museum but I understand why. I can keep dreaming!

No museum is perfect, and a thoughtful institution is always experimenting. Here are a few constructive suggestions that came to mind after my visit. There could be deeper provenance narratives for global objects. The Native North American and other world cultures collections are a great strength, the museum could further amplify voices from source communities (digital loans, collaborative labels, or co-curated displays). This would modernise interpretation and respond to ongoing debates around provenance and repatriation. I would also like to see increased interactive digital layers or opportunities. Many visitors now expect richer digital engagement (AR labels, deeper online catalogues, audio testimonies) in order to help with learning and accessibility. Increasing the online 3D/photographic access to specific artefacts would help remote researchers and casual online audiences. The museum already has a digitised collections portal, expanding it would pay dividends. Finally, expanded contemporary narratives. The ‘Story of Hastings’ format is excellent, building a rotating contemporary-history case (e.g. migration, modern fishing practices, climate adaptation) would keep the local narrative current.

If you’re planning on visiting, I have some final tips for you. A relaxed visit of 60–90 minutes lets you get into the major galleries without rushing. The museum is excellent for kids, hands-on displays and fossil content are a hit but do be careful as these busier galleries can cause bottlenecks which is why I navigated the museums in a non-linear fashion. As stated elsewhere, entry is free, which makes repeated visits easy. I’m already planning my return visit! Finally, the museum is a short walk from seafront and the old town which allows you to experience some of the history and culture you have just read all about. Hastings Museum & Art Gallery is a model of what a regional museum can be: proudly local but internationally minded, educational but inviting, and serious about collections while still keeping space for playful family learning. Its strengths are the tangible connections it makes between objects and place, such as fossils dug up on local shores. The Native North American collection is a standout: an unexpected depth that pushes the museum from ‘local curiosity’ to ‘repository of surprising significance’.

If you’ve visited the museum I would love to hear what your thoughts were and if you had a favourite gallery or specimen/artefact.

If you liked this post and enjoy reading this blog, please consider supporting me on Patreon where you will also gain access to exclusive content. If you enjoy reading my blog, why not subscribe using the form below?