Despite the fact my mum lived in Braintree for over a decade, I never actually visited the local museum. At the time I wasn’t the biggest fan of local museums and was unaware of their significance. So, I decided to visit recently and right this wrong. The Braintree District Museum (often called Braintree Museum) is the local history museum for Braintree and its surrounding district, housed since 1993 in the former Manor Street School building. The museum’s mission is to conserve and celebrate the area’s industrial, social and natural history, and it does that through a mixture of permanent displays, specialist collections and rotating exhibitions that draw on donations, archaeological finds and company archives. The museum occupies the Victorian Manor Street School (a gift to the town from the Courtauld family in the 19th century). The attractive red-brick building itself is part of the visitor experience and helps set the scene for the schoolroom, local industry and community displays.

Archaeology is one of the museum’s richest areas of collection. Prehistoric material such as Stone Age flint hand-axes and Bronze Age axe heads highlight the earliest human activity in the region, dating back to the Neolithic period, which testify to the presence of early farming communities exploiting the fertile soils of mid-Essex. These artefacts show how people cleared woodland, cultivated crops and crafted implements that supported everyday survival. By the Iron Age, settlement in the Braintree area had become more established, with evidence of enclosures, pottery and metalwork indicating organised communities engaged in farming, craft production and trade. The discovery of quern stones for grinding grain, along with fragments of decorated ceramics, points to a society with developing domestic and ritual traditions.

The Roman period is one of the most vividly represented chapters in Braintree’s archaeology, thanks to large-scale excavations carried out in the 1980s that revealed the remains of a substantial Roman settlement beneath the modern town. Finds from these digs, many of which are now displayed in Braintree District Museum, include pottery vessels, brooches, coins and domestic objects that illustrate the daily lives of the inhabitants. Building materials such as tesserae and tile fragments suggest the presence of well-constructed houses, while evidence of roadside activity indicates that Braintree lay on an important Roman route linking Colchester (Camulodunum) with St Albans (Verulamium). The range of artefacts points to a community that was integrated into wider economic and cultural networks, adopting Roman fashions and technologies while maintaining local traditions. These discoveries highlight Braintree as more than just a rural outpost, it was a thriving settlement whose prosperity in the Roman era helped shape the town’s later development.

The medieval story is told through coins, ceramics and artefacts from nearby sites, including finds associated with Cressing Temple, which help situate Braintree within the wider medieval economy and religious landscape. Beyond human history, the museum explores the natural environment of the district. Collections of fossils, geological specimens and displays on local wildlife help visitors understand the natural history that has shaped Braintree’s landscape. These exhibits are frequently used in the museum’s education programmes, encouraging children and families to think about the connections between the natural world and human activity. To me, I don’t think many visitors will connect the Roman and Medieval dots to the Braintree they know and are familiar with, as most people tend to think that settlements in these time periods were restricted to certain areas, rather than being quite widespread. The museum does a fantastic job of trying to reconnect visitors to the history that helped shape the local area.

I am also embarrassed to say that I didn’t know that John Ray (1627–1705) was born and lived locally. Ray is often described as the ‘father of English natural history’, and his life and work have strong connections to Braintree and its surrounding villages. Born in the nearby village of Black Notley, just outside Braintree, Ray grew up in the Essex countryside that would inspire much of his lifelong passion for plants, animals and the natural world. He was educated at Braintree Grammar School and went on to study at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he eventually became a fellow and lecturer. Despite his later academic career, Ray’s formative years in the fields and woodlands of Essex left a lasting imprint, and he retained a deep interest in the flora and fauna of his home region throughout his life. I know Ray for another reason, the Ray Society. The Ray Society was founded in 1844 by George Johnston in honour of John Ray, its purpose is to publish works in natural history (covering botany, zoology, fauna, flora, taxonomy, monographs, translations and facsimiles) especially where works are scientifically important but not commercially viable in mainstream publishing. Over its history it has produced well over 170 volumes, including George Albert Boulenger’s two-volume work, The Tailless Batrachians of Europe, published in 1897.

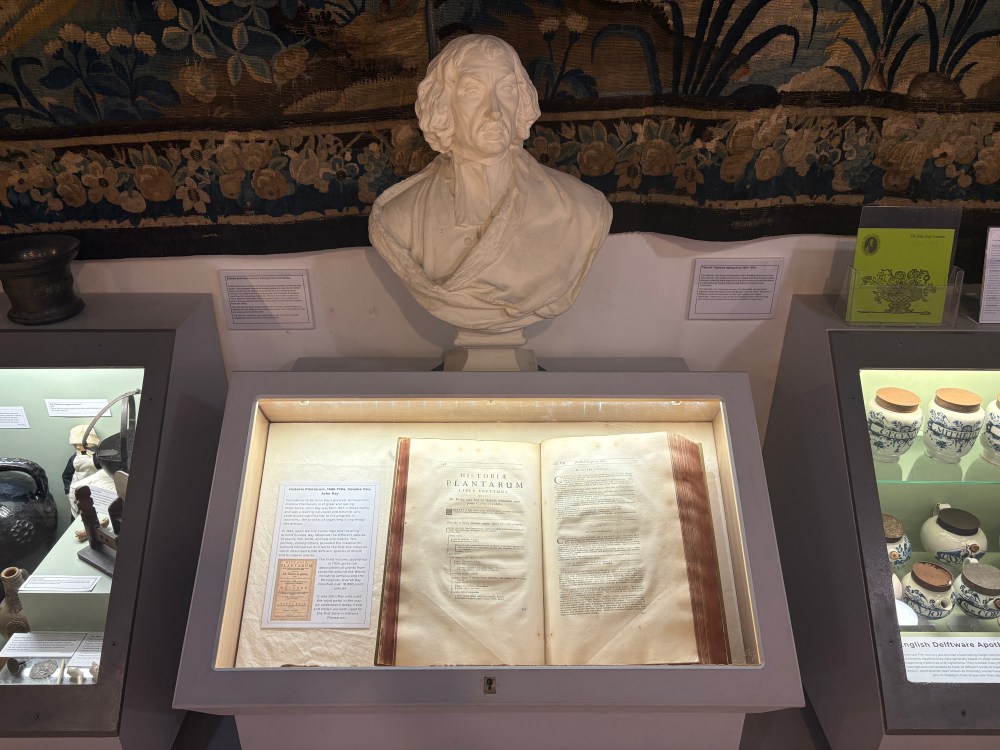

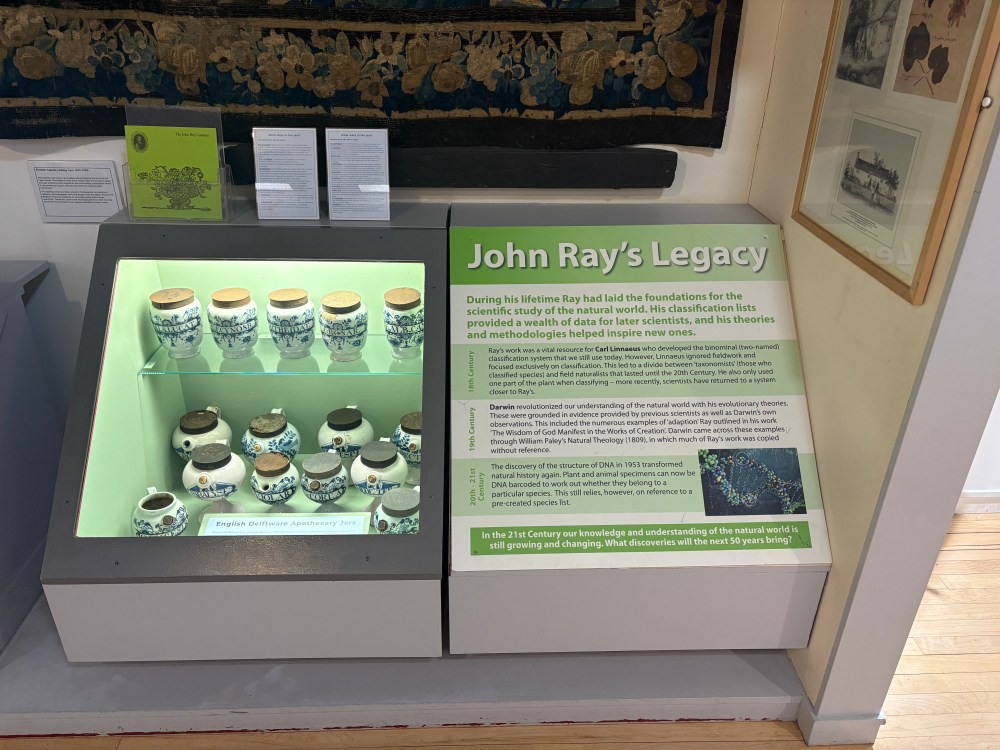

Ray’s most enduring contribution to science was his systematic classification of plants and animals. In an age when natural history was still governed by inherited medieval ideas, Ray sought to create an organised framework based on direct observation. His publications, most famously Historia Plantarum (1686), laid the groundwork for later taxonomists, including Carl Linnaeus, by defining the concept of ‘species’ in biological science. He travelled widely across Britain and Europe to collect specimens and record data, but his own Essex environment remained a constant point of reference. The hedgerows, meadows and wetlands of the Braintree district provided him with countless examples for study, and many of his plant records can be directly linked to the landscapes he knew as a child.

Ray also wrote on subjects beyond botany. His works on zoology, ornithology and natural theology sought to demonstrate the order and design of the natural world. For him, careful study of plants and animals revealed evidence of divine creation, and his writings shaped both scientific and theological debates of the late 17th century. His The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of Creation (1691) was widely read and influential, balancing careful observation with spiritual reflection. The legacy of John Ray is still visible in the Braintree area today. His birthplace at Black Notley is marked, and the village has celebrated his contributions through plaques and commemorations. The surrounding countryside, much of which still retains the fields and hedgerows he once studied, continues to be a living reminder of his work. The Braintree District Museum highlights Ray as one of the district’s most important historical figures, displaying material that connects visitors to his life and achievements. In doing so, the museum not only situates Ray within the history of science but also within the fabric of local heritage, underlining how a boy from rural Essex helped lay the foundations for modern biology.

The museum’s social history collections are brought to life through immersive reconstructions and personal stories. Chief among them is the Victorian schoolroom, a faithfully re-created classroom complete with period furniture, blackboards and school equipment. This space allows visitors, especially school groups, to experience the atmosphere of education in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The 20th century is represented through displays on both World Wars, incorporating uniforms, personal effects and oral histories that reveal how global conflicts touched everyday lives in Braintree. Complementing these are holdings of photography, ceramics and fine art, which capture local people, places and craft traditions. These collections help to round out the story of the district, offering insight into its cultural and domestic life as well as its industry.

In addition to its permanent galleries, Braintree Museum hosts a changing programme of temporary exhibitions. These displays often link broader historical or scientific themes, such as extinction, industrial design or scientific discovery, to the museum’s own collections. They are designed to be engaging for families and children, with interactive and hands-on elements that encourage active learning. Regular updates on the exhibition schedule make each visit potentially different from the last. It was due to one of these on extinction, that was the main reason for my visit. Extinction is running from 26th July through to 20th December 2025, so make sure you go and visit if you can. It is an interactive showcase that explores the science and history of extinction, aimed at younger visitors. It asks what extinction is, how it has occurred in the past, and how human actions influence it in the present, while also encouraging visitors to think about what can be done to protect species in the future. By combining fossil specimens, reconstructed creatures and interactive elements, the display bridges natural history with urgent contemporary themes of conservation. Extinction will be covered in its own separate post in a couple of weeks time, so please keep your eyes out for it!

The museum devotes significant space to Braintree’s industrial history, especially its textile and manufacturing industries. The town developed as a centre for woollen cloth production, with Flemish weavers settling in the area during the 14th and 16th centuries, bringing advanced weaving skills that boosted both quality and reputation. By the 17th and 18th centuries, Braintree was well known for its silk and woollen fabrics, and the industry expanded further in the 19th century when the Courtauld family established large silk mills in the town. These mills became the main employers in Braintree, drawing workers from surrounding villages and even from further afield, transforming the town’s economy and social structure. Courtaulds grew into one of the largest textile companies in Britain, with innovations in both silk and, later, man-made fibres. Although the decline of the textile industry in the mid-20th century led to mill closures and economic shifts, Braintree’s architectural and social landscape still reflects this rich heritage, with mill buildings and workers’ housing standing as reminders of its textile past. One highlight is the material from Warners, the prestigious silk and textile firm that supplied designs for royal commissions. Examples of fabrics and archival items showcase the company’s artistry and influence.

Alongside textiles, the story of Crittall Windows offers a different facet of industrial achievement. In case you’re wondering, Crittall Windows has its roots in Braintree where in 1849 Francis Berrington Crittall purchased an ironmongery on Bank Street, launching what would grow into a globally-renowned steel-window manufacturer (I’d not heard of them). After his death in 1879, business passed temporarily to his eldest son Richard, but by 1884 his younger son Francis Henry Crittall took over and pioneered the manufacture of steel-framed windows. As operations expanded, the company outgrew its original premises and in 1894 established a new works between Coggeshall Road and Manor Street in Braintree. By 1919 a factory was opened in Witham to help meet demand, especially for government housing after the First World War. Francis Henry was also a social reformer: recognizing the growth of the workforce and housing shortfalls in Braintree, he founded Silver End, a model village (between Braintree and Witham) in the late 1920s, with decent housing, infrastructure and amenities for employees. Over the decades, Crittall diversified its product range, introduced innovations (such as slimmer glazing bars via the “fenestra joint”), built galvanising capability, and expanded both in the UK and overseas. The company also contributed to war production in both world wars and is still trading today. I wonder how many local residents are aware of this important local connection?

Another local engineering company that the museum highlights is Lake & Elliot. This was a prominent engineering and foundry firm based in Braintree, active from the late 19th into the 20th century. The business was founded during 1894 by William Beard Lake and roughly three years later Edward Franklyn Elliot joined as partner, the company becoming Lake & Elliot. They operated from sites including the Albion Works and Chapel Hill Foundry in Braintree. Lake & Elliot’s product range was wide: they made tools and machinery for the cycle trade (such as spoke drills), motor accessories (including motor jacks under the ‘Millennium’ trade name), and also produced steel and iron castings for automotive and repair sectors. Over time they expanded their foundry facilities, including installing an electric steel foundry at Chapel Hill, and acquiring other companies (such as Fitall Gear, Cockburns, Hindle Valves) to widen their capabilities. During both World Wars, Lake & Elliot contributed significantly to war production in Braintree: they made components for tanks, military vehicles, aeroplane engines, and large numbers of vehicle jacks (one of their more famous outputs) that were standard issue. The firm continued operating through much of the 20th century, though ownership changes, acquisitions, and industrial decline eventually eroded its presence.

Finally, the ceramic tradition in Braintree, particularly the work of Edward Bingham of Hedingham, stands out as an interesting chapter in the town’s industrial and artistic heritage. Edward Bingham (1829-1914) was born into a pottery family and evolved from making purely utilitarian wares to producing ornate, decorative pieces inspired by archaeology, classical antiquity and local landscapes, items such as vases, urns, tygs, wall plates and garden wares, some embellished with historic or nature-based motifs. He founded the Headingham Art Pottery (later, under the Essex Art Pottery Company from 1901 to 1905), combining regular agricultural and functional ceramic production (crocks, pipes etc.) with his more artistic creations. Though the Essex Art Pottery was relatively short-lived, its pieces are now valued as examples of Victorian art pottery, and Braintree Museum preserves a substantial Edward Bingham collection which illustrates his experimental techniques with glazes, clay bodies and decorations.

Braintree District Museum offers a compact but rich journey through thousands of years of local history. Its archaeological collections place the town in the deep timeline of human settlement, while the industrial holdings (particularly the Courtauld, Warner and Crittall material) demonstrate its role as a centre of design and manufacturing. Immersive experiences such as the Victorian schoolroom and the exploration of John Ray’s natural history legacy provide vivid entry points for visitors of all ages. Combined with the charm of the historic building, these collections make the museum a rewarding destination for anyone interested in the interplay of community, industry and environment. It is worth visiting if you’re in the area, the £4 entry fee is well justified especially in light of the temporary exhibits the museum also hosts.

If you liked this post and enjoy reading this blog, please consider supporting me on Patreon where you will also gain access to exclusive content. If you enjoy reading my blog, why not subscribe using the form below?

1 COMMENTS